Kolkata: There is apartheid going on not only by Israel in Gaza but also in India’s own national capital Delhi and in West Bengal’s capital Kolkata, claimed activist and CPM leader Saira Shah Halim.

Speaking at the launch of Indian Muslims’ Tryst with Democracy: Challenges and Opportunities, Saira — considered a moderate voice in political circles — spoke at length about the challenges Muslims face in Bengal, across India, and globally.

Saira Shah is the wife of doctor and politician Fuad Halim, daughter and sister of army veterans Zamiruddin Shah and Mohammed Ali Shah, and niece of acclaimed actor Naseeruddin Shah. A well-known face on television news debates, she has fought two elections on the CPM ticket — one for the Lok Sabha and another for the West Bengal Assembly, where she contested against Babul Supriyo.

Homogeneity is a Big Fallacy

She began by dismantling what she called the “myth of Muslim brotherhood.”

“The ongoing genocide in Palestine and Gaza has made it clear that there is no brotherhood among Muslims, as it would have not gone so far,” she said.

Bringing the point home to India, she added, “Indian Muslims are divided by language, sub-sects, and castes as well. There is no Ummah (Muslim brotherhood) existing in practice among Muslims today. There is no homogenization either. Indian Muslims are divided on caste lines like Hindus, and also along sectarian lines.”

Housing Apartheid in South Kolkata

The “moderate” leader then took a firm stand on discrimination in housing.

“People say about Israel’s apartheid, but there is apartheid in Delhi. It is not so much in Kolkata. But there is housing apartheid in South Kolkata. Be a Muslim and try to get a house in South Kolkata, you will not get it. People say Muslims are getting ghettoized, but do Muslims have a choice? We are still facing the ghost of partition of 1947,” she said.

Saira was equally clear about why she is outspoken.

“People also say, why are you so political? Point is, is there any choice? Today, if a Muslim does not raise the voice, he or she is being complicit in the crime against Muslims — not only in India but globally.”

Her more than half-hour-long speech touched on Umar Khalid still being in jail, the lynching of Muslims, and arrests over tweets. She also criticised MPs elected on minority votes but silent on critical issues:

“Muslims are almost 30 percent in Bengal, but do we ever think that our representing MPs — who may not be Muslim but secular — are remaining absent when the Anti-CAA Bill was debated, when Article 370 was revoked?” she asked, hinting at TMC MPs who skipped key sessions on Muslim concerns.

Education and Healthcare Neglect

Professor Abdul Matin of Jadavpur University drew attention to how micro-level changes could uplift Muslims and other marginalised groups.

“It is often said that Muslims are lagging behind in education. And it should improve. But how will it be improved? When Muslims are earning 8 to 10 thousand a month, how will they send their sons and daughters to private schools? They will go to government schools — and these have deteriorated so much that, after studying there, the community’s children will not rise,” he said.

Matin added that the problem is not confined to rural Bengal but also exists in major Muslim areas of Kolkata — Metiabruz, Khidirpur, Topsia, Park Circus, and Raja Bazar.

“Kolkata Municipal Corporation used to run schools, which no longer function,” he noted.

The public education system in Bengal, he said, has not been strengthened, affecting all low-income groups — with Muslims among the worst hit. Political interference, past and present, compounds the problem: “If you are not part of this or that political party, it will…” he left the sentence hanging, implying systemic bias.

Healthcare, he added, is equally grim. “People from rural Bengal travel from far away and queue from midnight to see a doctor or get admitted. We should stress on local mohalla schools and clinics.”

‘Jo BJP Nahi Kar Paya, Wo TMC Ne Kar Dikhaya’

Prof Matin also accused so-called secular parties of fusing politics and religion.

“I am against any government dole for religious activities. But now Mamata Banerjee’s government has not only built a temple in Digha with government funds but spent billions on its advertisement to invite devotees. The government even used the Public Distribution System (PDS) to distribute Prasad. This has not even been done by any BJP government so far,” he remarked.

Education Over Religion

Former Rajya Sabha member and bureaucrat Jawhar Sircar stressed that education — not religious symbolism — was the path to advancement for Muslims.

“Muslims must not be allowed to be used as vote banks and must boldly join the democratic, secular forces who are fighting to restore the plural India we were born into,” Sircar said.

He also urged patience over the caste census. “Caste Census can be a game changer for Muslims too, so wait for 2026 and let the Census report get released,” he advised.

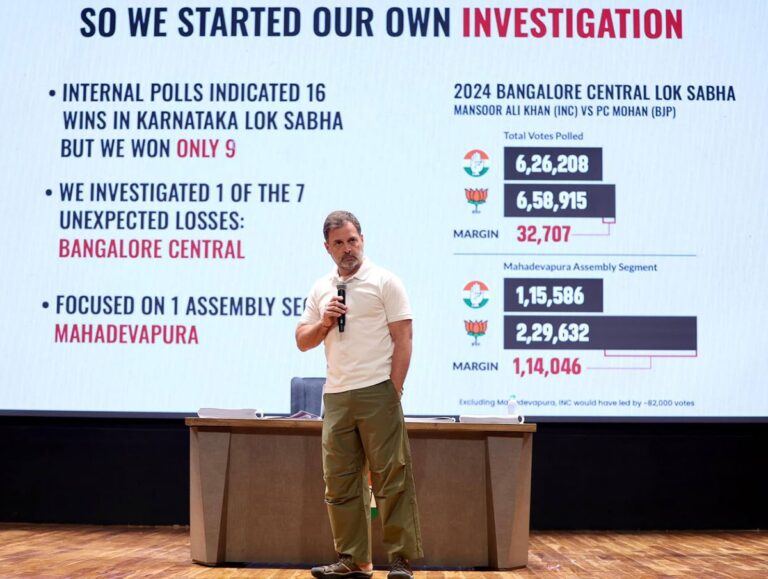

Declining Representation

Prof Maidul Islam of CSSSC (Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta) noted that Muslims are democratically conscious due to their vulnerability but face systemic barriers. He pointed to a sharp decline of Muslim representation in Lok Sabha started from 1980 and in Bengal assembly from 2011, saying political parties deliberately exclude them from candidacy — a practice Ambedkar had warned about.

He also linked the lack of progressive leadership to the community’s woes and criticised Hindi cinema for stereotyping Muslims as gangsters with clichéd appearances.

Why This Book Matters

The book’s author, Prof Syed Ali Mujtaba, explained why he felt compelled to write it and said the future actions outlined were grounded in solid research.

Activists Imran Zaki and Manzar Jameel also offered their insights, while Humaira Jawed moderated the session.