[dropcap]“B[/dropcap]ahut Samjhe the Hum Is Daur Ki Firqa Parasti Ko

Zubaan Bhi Aaj Shaikh -o-Brahaman Hai Ham Nhi Samjhe” (Rashid Banarsi)

Around 225 years ago, in the city of Calcutta (now Kolkata), the seeds of division between the Urdu and Hindi languages were sown with the establishment of Fort William College. The British colonial administration introduced separate language primers and translated Persian and Sanskrit texts into Urdu and Hindi, which were distinguished primarily by their scripts. This bifurcation laid the foundation for a divide that later deepened through the politicization of language and the eventual religious association of Urdu with Islam.

Ironically, in the present context, one of the most prominent institutions associated with the development and promotion of Urdu, the West Bengal Urdu Academy, succumbed to similar tendencies. The Academy was scheduled to organize an event titled “Urdu in Hindi Cinema” from August 31 to September 3. The event aimed to explore and celebrate one of the most vibrant and influential cultural spaces where Urdu has thrived. Hindi cinema has long served as a transnational vehicle for embracing Urdu, helping to preserve its beauty, idioms, and lyrical richness across linguistic and religious boundaries. However, the event was postponed following pressure from two Muslim religious organizations. Their objection stemmed from the inclusion of celebrated lyricist Javed Akhtar, whose offensive and dismissive remarks about Islam have often sparked controversy.

The decision to postpone the event in response to these objections raises serious questions on different points. First, the dismissive use of Urdu cultural spaces by a few literary figures affects the inclusive and tolerant nature, as well as the tradition of refined literary expression within the Urdu language. Secondly, the encroachment of linguistic and cultural institutions by religious bodies. Third, the independence and credibility of the organization involved in the preservation of Urdu, and lastly, the future of Urdu itself.

When Faith Overrides Language

It is important to mention that religious organizations are partially precise in terms of their right to express discontent with views they find offensive related to faith. Although it should be based on constructive dialogue with mutual respect for those who differ and should not be selective. In a democracy, dialogue, dissent, and critique form the bedrock of civil society. Likewise, cultural figures such as Javed Akhtar also bear a responsibility to engage with belief systems respectfully, especially in public or institutional spaces. Insensitive or derisive remarks, regardless of intent, risk alienating audiences and undermine the spirit of constructive engagement. In today’s communally polarized climate, such remarks are often weaponized—not just to critique individuals but to vilify entire communities.

Therefore, as a public intellectual, these things must be taken into consideration, and unnecessary derision of beliefs should be avoided in serious literary or cultural discourses. And in terms of spaces related to Urdu, it adds woes to the already diminishing circles and risks undermining the effectiveness of intellectual engagement.

Javed Akhtar and the Burden of History

However, the choice of the Urdu Academy as the platform by a religious organization to register such objections is also deeply problematic. It puts the language and institutions dedicated to its survival and growth in a precarious position. Urdu, unlike Arabic, holds no intrinsic religious sanctity. In fact, during the 15th and 16th centuries, when the language existed in its early forms like Hindavi or regional variants such as Dakkani, it was considered unsuitable for religious writings. It was only in the 18th and 19th centuries, during the reformist movements, that Urdu began to be employed for religious discourse.

The association of Urdu with Islam was further cemented during the colonial period, when the language emerged as a symbol of Muslim identity. This perception, however, ignored the diversity within the Muslim community—spanning sectarian, class, ethnic, and linguistic lines. The post-colonial fate of Urdu has been shaped by these historical legacies. In Pakistan, despite being the mother tongue of less than 10% of the population, Urdu was declared the national language and used by the Punjabi elite to suppress other ethnic languages like Pashto, Sindhi, Balochi, Saraiki, and Bengali. In India, Urdu too faced structural neglect, primarily due to its association with a religious minority and its stereotyping as the language of Islam. However, there have been continuous efforts to challenge the sectarian appropriation of Urdu within academic and cultural circles.

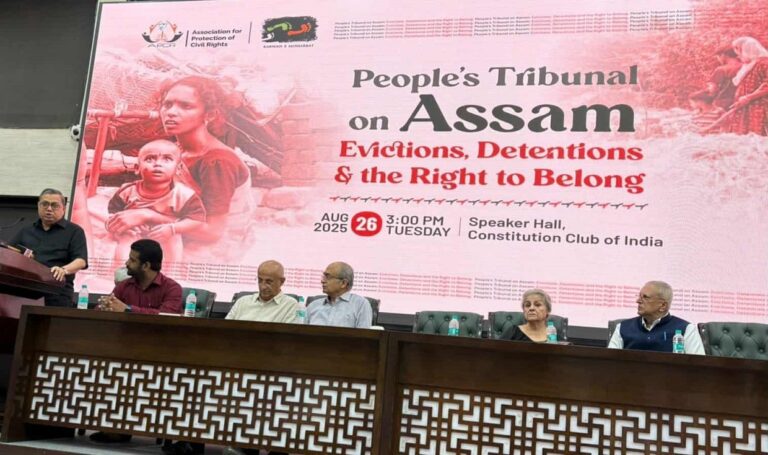

Religious institutions have undoubtedly contributed to sustaining this language, but their intervention in secular institutions, as represented by this incident, would restrict the relevance of Urdu to a theological domain. This would, in turn, lead to the overshadowing of the secular literary and cultural dimensions of Urdu by religious connotations. It would reinforce the stereotyping of Urdu as inherently Islamic, thereby resulting in alienation of the non-Muslim Urdu speakers or their well-wishers.

Moreover, it would hinder the potential of Urdu to serve as a bridge across communities, particularly in the already dwindling state of multicultural spaces. And most importantly, this trend demonstrates a dangerous precedent of subordination of cultural and literary discourse to theological gatekeeping.

The decision by the West Bengal Urdu Academy to postpone its program under religious pressure is yet another blow that deserves lamentation. It undermines the Academy’s credibility and its stated purpose: to promote and preserve the Urdu language. This surrender to the religious bodies represents a failure of institutional responsibility, which is the norm of the day in West Bengal these days.

The Academy, which enjoys patronage and access to significant resources, is one of the few state-supported institutions dedicated to Urdu in India. Its responsibilities are therefore magnified, as it is expected to safeguard Urdu from political neglect as well as sectarian appropriation. At a time when Urdu faces unprecedented politicization and has become, unjustly, a target of hate, the surrender of one of its key institutions to sectarian interests is indeed troubling. It is a symbolic blow to every voice that envisions the safeguard of Urdu as an essential endeavor in line with the preservation of India’s pluralist and democratic identity.

Safeguarding Urdu’s Plural Legacy

Therefore, it is crucial to delineate religious and secular-cultural spaces when it comes to language. Historically, before being appropriated as a symbol of religious identity, it drew heavily from secular, syncretic, and humanistic traditions. The interplay between its secular and religious dimensions should be acknowledged and preserved, not manipulated to serve ideological ends.

The space for Urdu must be reclaimed as an inclusive, pluralistic domain along with the upkeep traditions of Tehzeeb to foster sensitivity and empathy within its dwindling spaces. More than just a language, Urdu is a cultural and historical legacy that belongs to all Indians regardless of religion. Urdu institutions and the wider Urdu-loving public must remain vigilant and assertive. Cultural programs, literary events, and educational initiatives must continue without fear of ideological backlash.

Most importantly, Urdu must be re-situated within India’s broader democratic and pluralist ethos and should be celebrated not as a communal relic but as a living, evolving, and inclusive language.