[dropcap]W[/dropcap]hile watching Rahul Gandhi and Priyanka Gandhi’s dazzling roadshow in Bihar, I couldn’t help but wonder—if the Gandhis are working so hard for Bihar, why don’t they show the same concern for West Bengal? The answer became clear soon enough, when I saw the list of newly announced committees of the West Bengal Pradesh Congress.

Bihar is less than 600 kilometres away from Bengal, but Rahul Gandhi’s much-touted slogan—“Jitna Aabadi, Utna Haq” (the share of representation should match the share in population)—seems to lose all meaning when it comes to Bengal. After all, Muslims make up nearly 27 percent of Bengal’s population. By that logic, they should have at least 27 percent representation in any Congress committee in the state. One could even round it up to 30 percent, given that Congress’s only surviving strength in Bengal lies not in Kolkata but in the Muslim-majority districts of Murshidabad, Malda, and North Dinajpur. Put simply, Muslims should naturally expect at least one-third representation in the West Bengal Pradesh Congress Committee.

From Slogan to Empty Numbers

But a closer look at the Pradesh Congress’s newly announced lists shows how Rahul’s formula has been reduced to an empty slogan here. Perhaps, after spending ten long years in alliance with the CPI(M), the Congress leaders at Bidhan Bhavan (the party’s Bengal headquarters) have also started believing that the party should be dominated by Chatterjees, Bhattacharyas, and other upper-caste Hindus. Why do I say this? Because in the Political Affairs Committee—arguably the most important one—out of 48 members, only 4 are Muslims from Bengal. Even if you count the two Muslim representatives sent from Delhi, the total rises only to 6 out of 48. That’s still below 10 percent.

The Pradesh Election Committee, which will oversee the 2026 polls, has 67 members—only 7 of them Muslims. Subtract the two from Delhi, and Bengal Muslims are left with just 5. In the 86-member Executive Committee, Muslims are only 7. Among 35 vice-presidents, Muslims number 5. In the list of 29 general secretaries, there are 5 Muslims. Out of 48 organisational secretaries, 14 are Muslims. And out of 33 district presidents, only 4 are Muslims. Does this reflect the state’s 27 percent Muslim population? Or is Bidhan Bhavan simply following Alimuddin Street (the CPI(M) headquarters) in prioritising upper-caste Hindus?

Discontent Within the Ranks

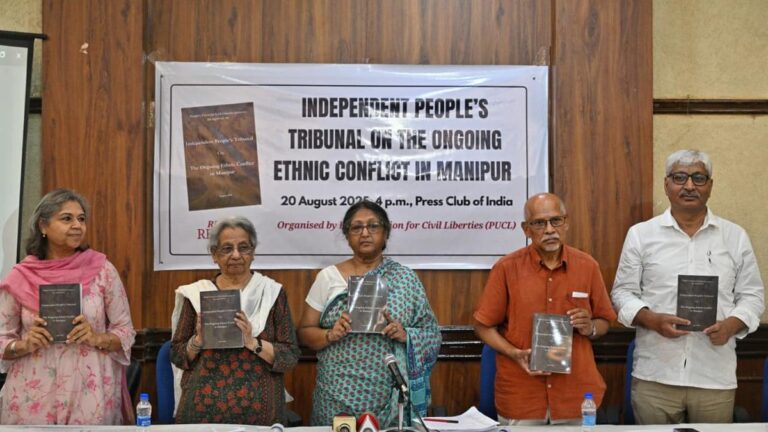

Unsurprisingly, many Muslim Congress supporters are fuming. Some are unwilling to speak publicly, but leaders like trade unionist Anwar Ali Khan and Samir Alam have already held press conferences, presenting the numbers to show just how little representation Muslims are being given. Their point is hard to deny. If in the two most important committees—Political Affairs and Pradesh Election—Muslims are less than 10 percent, how credible are these bodies? Why should the Muslim voters of Murshidabad, Malda, or North Dinajpur believe that Congress is serious about them?

Rahul Gandhi may well want to empower minorities, and in states like Karnataka and Assam, the Congress has made an effort to include Muslim leaders in proportion to population. But in Bengal, the Pradesh Congress seems far from that vision. And that distance may explain why Muslims here remain equally distant from the party. If Malda and Murshidabad Muslims ask why they should see Congress as a safe political home—and not Trinamool—the Pradesh Congress has no convincing answer. In fact, if Mamata Banerjee studies these numbers, wouldn’t she be more determined to sweep away minority votes in those districts?

After Anwar Ali Khan and Samir Alam’s press conference, Congress leaders tried to defend themselves. Ironically, they sent a Brahmin leader to address the media, who claimed that “every community” had been given proper representation. But numbers don’t lie. And in this case, the numbers cut deep.

Why Mamata Still Holds the Minority Ground

Since the Sachar Committee Report, Bengal’s Muslims have consistently drifted towards Mamata Banerjee. Neither the Congress nor the CPI(M) has found a way to win back their trust. Putting up faces like Naushad Siddiqui here and there may help with optics, but the overall numbers show who actually holds power in the party. Sadly, Bidhan Bhavan seems just as blind to Rahul Gandhi’s “Jitna Aabadi, Utna Haq” slogan as Alimuddin Street.

Even the BJP, despite not caring for Muslim votes, ensures caste and community balance when it distributes leadership roles. Leaders like Suvendu Adhikari keep reminding that they welcome “patriotic Muslims.” But what does the Bengal Congress offer? When the party’s committees fail to reflect the state’s population, why should Muslims in Murshidabad, Malda, or Nadia trust them?

Rahul Gandhi’s growing popularity—especially after his fight against electoral fraud—has generated real excitement across India. Yet in Bengal, Muslims are asking: why should we trust Congress when its own leadership doesn’t trust us with proportional representation? If the Congress in Bengal is reduced to just a “signboard party,” much of the blame may lie in these very lists of office-bearers and committees.

And perhaps that is why, once again, Muslims across Bengal—from North 24 Parganas to Nadia, from Malda to Murshidabad—are looking back to Mamata Banerjee to safeguard their political future.

It is a translation of a piece published in Bangla.