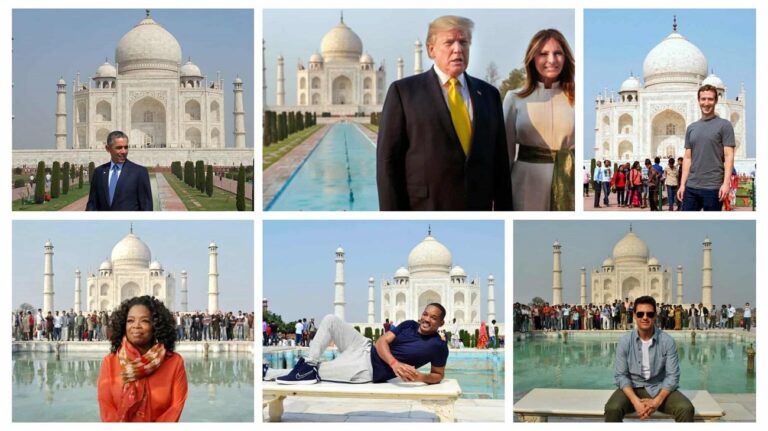

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he Taj Mahal, regarded as one of the Seven Wonders of the World, is one of the major markers of India on the world map. It is a poem in marble; Gurudev Rabindranath Tagore described it as “a drop of tear on the cheek of time.” Its beauty and fascination as a symbol of love are remarkable. It is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and is maintained by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI). A marvel in marble, its replicas have often been given as gifts to visiting heads of state.

Since it was constructed by the Mughal ruler Shah Jahan in memory of his wife Mumtaz Mahal, it has been an eyesore to the Hindu right wing. Though its history has been settled by the ASI—and even the Culture Minister Mahesh Sharma said in 2017, during the Modi regime, that it was not a Shiva temple—the controversies are deliberately raised time and again by right-wing leaders and ideologues to boost communal divides. The ASI has repeatedly clarified that it is a mausoleum, not a temple.

Right-Wing Attempts to Rewrite History

The first major controversy around it was created when Yogi Adityanath became the Chief Minister of Uttar Pradesh. His tourism department published a booklet about sites of tourist attraction in the state, but it did not mention the Taj as one of them, despite nearly 12,000 visitors being attracted to this marvel daily. The monument draws 23% of all tourists to India. When questioned, Adityanath retorted that the Taj does not reflect Indian culture.

Now, another film by Paresh Rawal is set to be released. Its trailer shows that as the dome of the Taj is lifted, Lord Shiva appears. The forthcoming film, The Taj Story, as it appears from its trailer, is an attempt to propagate the idea that the Taj is Tejo Mahalaya, a Shiva temple that was converted into a tomb by Shah Jahan.

The argument of the film is that the Taj was a Hindu temple—Tejo Mahalaya—built in the 4th century (later revised to the 11th century) and converted into a mausoleum by the Mughal ruler Shah Jahan. The claim that it was a 4th-century temple was first put forward by a lawyer, PN Oak. Historian Ruchika Sharma has rubbished Oak’s theory on the basis of historical evidence: “Oak, who did not know Farsi, perhaps missed this vital detail that refutes his theory of the Taj being a reused 4th-century palace.” Historians such as Giles Tillotson have also challenged Oak’s theory, asserting that “the technical know-how to create a building with the structural form of the Taj simply did not exist in pre-Mughal India.”

The mystery of the 21 empty rooms at the bottom was also clarified by the ASI. Architecturally, they were built to provide stability to the structure and are used for maintenance purposes. This clarification, too, came during the Modi regime.

Once the 4th-century theory did not work, Oak revised it, claiming that it was a 12th-century temple. Sharma notes, “Yet, Oak armed himself with make-believe and propaganda and petitioned the Supreme Court of India in July 2000, claiming that the Taj was constructed by Raja Paramar Dev’s chief minister Salakshan in the 12th century and was therefore a Hindu structure, Tejo Mahalaya, and not made by the Mughals.”

Oak went up to the Supreme Court to make his point, but the highest court rebuffed his fantasy, which was bereft of historical evidence. His main arguments were based on the architectural aspects of the tomb—the dome at the top, the inverted lotus, and the 21 empty rooms at the bottom. Similarly, later, one Amarnath Mishra approached the Allahabad High Court, petitioning that it was built by the Chandela king Parmardi, but this was also dismissed by the court in 2005.

From PN Oak to Today’s Propaganda Films

There are detailed and impeccable historical accounts available about the construction of the Taj. Travelers Peter Mundy and Jean-Baptiste Tavernier mention that during their visit to India, they learned of Shah Jahan’s grief and his determination to build a grand structure in memory of his wife Mumtaz Mahal. Shah Jahan made elaborate plans, involving several architects—the chief architect being Ustad Ahmad Lahori, a Muslim, and one of his major associates a Hindu architect. Badshah Nama, the biography of Shah Jahan, provides a detailed account of the entire process and the group of people who planned and executed it.

The land chosen for the Taj had belonged to Raja Jai Singh. There are two versions of how it was acquired: one says that it was procured by giving due compensation; the other mentions that Raja Jai Singh gifted it to the emperor, as they were on friendly terms. The architecture of the Taj reflects the syncretic traditions that prevailed at the time. The double-dome structures were introduced by Mughal architects—examples include the Red Fort and Humayun’s Tomb. Earlier Hindu temples had triangular superstructures. Later, domes were also introduced in temples. Architecture is never an exclusive process; the mixture of architectural styles is part of the evolution of civilizations.

Nearly twenty thousand artisans were hired for the construction. As the Mughal administration had a dedicated construction division, the magnificent structures of North India were not sudden miracles. The rumor that the workers’ hands were cut off is baseless—there is no source to substantiate it. The account books and documents from Shah Jahan’s time clearly record detailed expenditures incurred in building the Taj, including the cost of Makrana marble and wages paid to workers. Some prevalent Hindu motifs were incorporated into the design, as Hindu architects and workers were also part of the construction process.

In a lighter vein, one should mention PN Oak’s fertile yet banal imagination, which placed the roots of all world civilizations in Hindu culture. For him, Christianity was Krishna Niti; Vatican came from Vatika; and Rome from Ram! Despite such superficial claims devoid of any historical evidence, he kept publishing books and pamphlets, which were circulated in RSS shakhas to propagate his theories until they became part of popular social understanding.

A Political Project Masquerading as History

Most of the points raised by the upcoming film (as seen in its trailer) about the Taj Mahal were clarified more than a decade ago. The revival of these falsehoods is a political move intended to serve the Hindu nationalist agenda by spreading hate against Mughal rulers—and by extension, today’s Muslims.

This film is yet another propaganda project in a series that includes The Kashmir Files, The Bengal Files, The Kerala Story, and others—each aimed at intensifying right-wing propaganda. The Taj Story will likely be yet another tool for divisiveness and hate that continues to dominate contemporary India.