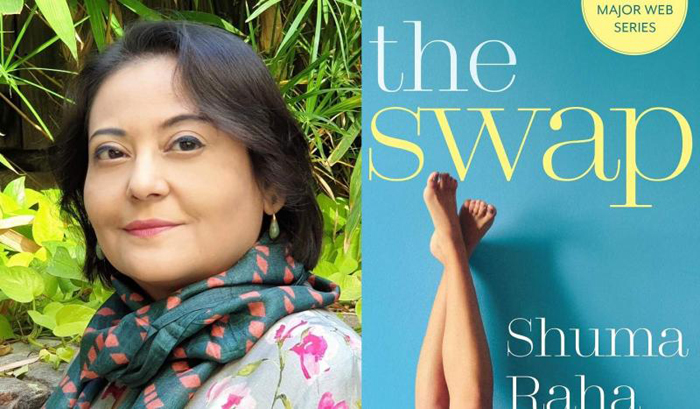

London Dreams, Kolkata Nightmares: Why the City Deserves Better, Not Bigger Promises

Fourteen years after the promise of a “London-like” Kolkata, the city is still marred by broken roads, encroached sidewalks, ugly rags, and vanishing parks. Garbage returns within hours of clearance, slums and makeshift stalls choke public spaces, and hospitals force the poor to sleep under open skies. Kolkata is not failing for want of vision, but because leaders ignore simple fixes in pursuit of hollow grandeur.

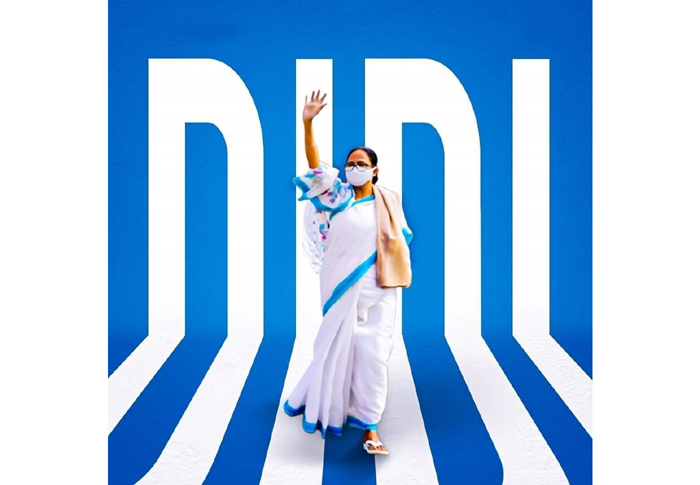

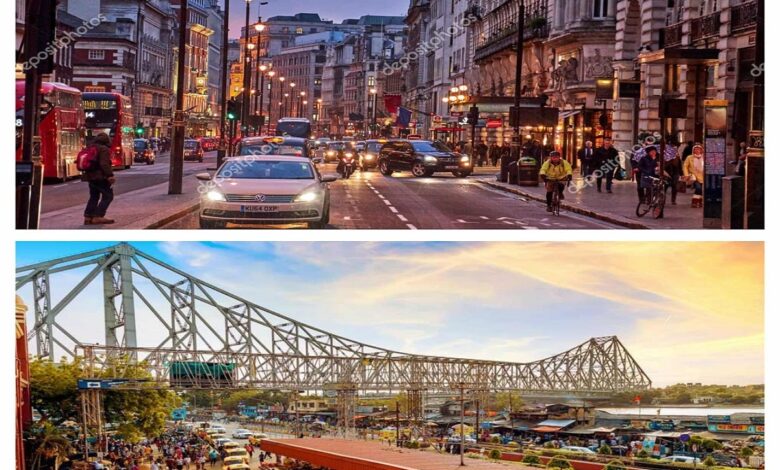

Some 14 years ago, the Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee had promised to convert Kolkata into London, and she also made a recent visit to the great city. However, we really don’t know when this will happen, and, frankly, our only hope is that our city sheds the stigma of being the world’s most unsightly capital. This is evident through heaps of garbage, ugly shanties right on main thoroughfares, and rags covering the pavement stalls.

Except for a few deserted streets, no sidewalk in this metropolis remains unclaimed by hawkers, occupied with a vengeance in the last few years. No, I am not just referring to Gariahat-Rashbehari, New Market-Esplanade, or Bidhan Sarani—these hawker-congested stretches have their own historic legacy, like when Mayor Prashanta Chatterjee and Minister Subhas Chakraborty tried their best to clear the encroachments through ‘Operation Sunshine’ — and failed. After every eviction drive, new stalls pop up, and only the rates paid to local leaders and police keep increasing.

In the recent past, not a single square foot of any major or minor street has escaped occupation by vendors. Such a massive plan to encroach on every sidewalk would have been impossible without the state’s grand patronage. This must be a covert government scheme to alleviate the distress of the masses. With no jobs available in Bengal for decades, this is surely the most fruitful employment scheme.

Sidewalks of Survival: Hawkers, Jobs, and a City on the Edge

Besides, the struggling middle class also requires cheap goods, so there’s little room for us to despair. Plus, there’s the Prime Minister’s stamp of approval—his ‘Street Vendor Scheme’ under which registered hawkers get lifelong occupation certificates and inheritance rights as well.

But where and how do ordinary people walk and navigate this mess on foot? If they trip, there’s the State’s Swasthya Sathi scheme for hospitalisation. We’ll never know how many crores the government of West Bengal spent on road repairs, but just a few showers are enough to wipe off the blacktop and bitumen, and stone chips simply roll away. Of course, tenders will be issued once again, and contractors selected after mutual agreements are worked out with those who rule. The same contractor will return soon, with road rollers, tar-melting equipment, and workers. As S Wajed Ali has said, “The same tradition continues forever.”

We cannot, of course, ignore the countless poor people who cook simple rice and dal for even larger numbers who survive by eating these at sidewalk stalls. But washing dishes in just a handful of water raises the risks of typhoid, cholera, and stomach infections. Can the ever-concerned chief minister, who already has so many schemes and plans, conjure just one more? Municipalities could then install clean water taps nearby and ensure that the dirty water from washing dishes drains directly into the sewers. Since there is no hope whatsoever of retrieving our sidewalks, we may as well ensure that the poorest sections are not afflicted by stomach ailments.

After some fires broke out at a few hawker sites, the municipal chief ordered the removal of all inflammable plastic and polythene sheets from roadside stalls. In several areas, tin structures were mandated, and they covered the two sides of the stalls and their roofs. But no orders were issued about how to cover the most visible street-facing rear-sides of stalls. So, hawkers cover these glaring sides with tattered bedcovers, patchwork dirty sheets, or even ungainly sarees. Thus, Kolkata soon earned the sobriquet of the “London of tattered rags”.

From Aesthetic Nightmares to Creative Possibilities

Following repeated requests, the municipal corporation started putting up signboards behind those stalls in some areas, announcing the benevolent chief minister’s numerous assistance schemes and her pictures with so many different smiles. Whether these boards are aesthetic or not is not for taxpayers to judge, but people travelling to vast stretches of roads are assaulted by the disgusting sight of tattered rags and dirty cloths covering hawkers’ stalls. Cannot we devise some more pleasant alternatives? If Kolkata is truly India’s cultural and creative capital, cannot its numerous artists be put to good use? Could we not persuade the Durga Puja clubs of every neighbourhood to organise creative art competitions to cover the distasteful road-facing rear-sides of the vendor stalls? After all, they are flush with funds as it is, and then receive the controversial government grants as well, and are always on the lookout to outdo their rival clubs. They could surely contribute to enhancing local aesthetics. Or, even commercial firms could sponsor such initiatives, like the way the Calcutta Electric Supply Corporation has beautified its junction boxes with imaginative artwork and tributes to greats. Can Kolkata not show its legendary vibrancy in street art?

Many areas of the city are occupied by makeshift slum-dwellings, covered with ugly black and blue plastic sheets. I don’t know who these homeless people are, but if they have to stay there, can the government not make their dwellings healthier and cleaner? We may not aspire, like Mamata Banerjee, to become London, but we can at least touch up the city here to prevent it from becoming an eyesore. If only those who rule us visited India’s other swank, gleaming cities, they would hang their heads in shame to see the depravity and sheer decay — with doddering about-to-fall buildings — that distinguishes Kolkata of the 2020s.

I stay opposite the late Mayor and Minister Subrata Mukherjee’s Ekdalia Street and recall how he would fume at the messy stuff, clothes, and beddings that rag-pickers had piled under the Gariahat flyover, which separates our localities. He has gone, but they remain where they were. If only some inexpensive storage boxes with locks were given to them, the whole area would look cleaner. Why do our rulers dream of global cities but ignore such small fixes?

Parks Lost, Playgrounds Gone: The Vanishing Green of Kolkata

Now, let us look at our parks and playgrounds. Almost none of the open spaces we played around in our childhood survive. Real estate is Bengal’s most lucrative business. There is no local leader who hasn’t amassed fortunes or flats from it. Municipalities have seized almost every park for their offices and infrastructure. So, where will the kids play, or the elderly breathe some fresh air? Mumbai still has its Nana-Nani parks — why can’t we? We do not want London—just give us our parks back.

We appreciate that garbage is cleared twice daily, but by the evening, streets are littered once again by educated residents and their un-civic maids. These smelly piles then host T20 matches for rats, moles, and cockroaches. Municipal authorities must either penalise the negligent residents or introduce a night-time cleanup round. These ugly piles are simply unbearable.

Speaking of the night, let us come to the hospitals. This regime has added grand European-style gates that can outdo rival cities. But, inside the premises, patients and families have to endure endless hours in the scorching sun or in heavy rain. At night, many thousands sleep on cardboard or flex sheets, pathetically waiting to see doctors the next morning. If the honourable chief minister could visit a hospital at night, she would see the miserable plight of the masses, and maybe also hear their stifled cries.