Jharkhand IAS officers tweet to make #JharkhandWithModi trend on Twitter

Ranchi: “Prabhat Tara Maidan is all set to welcome the honorable @PMOIndia sri @narendramodi for the launch of schemes that will redefine India 20 years from now”.

“After the creation of Jharkhand, for the first time, in Raghubar government only, schedule caste commission has been formed”.

“In the 108 Ambulance of Jharkhand, all the latest medical equipment are stalled including ventilator, basic life support system, so that patient’s life could be saved. So far, more than 2.6 lakh patients have got swift treatment”.

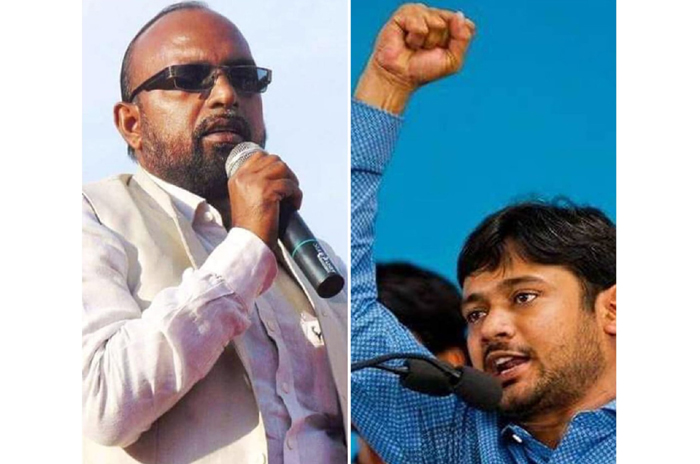

#JharkhandWithModi was also trending on Twitter for some time. Co-founder of Alt News, Mohammed Zubair tweeted on Thursday late night that at least 79 tweets were posted by Deputy Commissioners posted in Jharkhand. Some deputy commissioners like East Singhbhum DC (twitter handle @DCEastSinghbhum) posted 12 tweets. Besides them, the tweets with #JharkhandWithModi came from other deputy commissioners including DC Pakur, DC Chatra, DC Latehar and DC Koderma.

Above mentioned quotes are tweets, tweeted not from Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) workers or leaders, MP or MLAs, but from the handles of Indian Administrative Service (IAS) officers posted in Jharkhand. The first one is from DC Ranchi. The second tweet is from DC East Singhbhum. The last one is from DC Giridih.

Since Narendra Modi became the Prime Minister of India, in 2014, he has visited Jharkhand, many times and launched major schemes from the Tribal dominated state including Ayushman Bharat.

On September 12 too, PM Modi chose to launch farmer pension scheme—Kisan Maan Dhan Yojna from here. But, this visit of Narendra Modi was different, as apart from BJP leaders and Chief Minister of Jharkhand Raghubar Das, the Deputy Commissioners of different districts of Jharkhand were welcoming the Prime Minister, and highlighting Jharkhand government’s progress in different welfare schemes.

#JharkhandWithModi was also trending on Twitter for some time. Co-founder of Alt News, Mohammed Zubair tweeted on Thursday late night that at least 79 tweets were posted by Deputy Commissioners posted in Jharkhand. Some deputy commissioners like East Singhbhum DC (twitter handle @DCEastSinghbhum) posted 12 tweets. Besides them, the tweets with #JharkhandWithModi came from other deputy commissioners including DC Pakur, DC Chatra, DC Latehar and DC Koderma.

The opposition party and its leaders, especially Jharkhand Mukhti Morcha (JMM) and former Chief Minister Hemant Soren has tagged IAS Association and sought their intervention and to question how officers are compromising with the constitution and betraying the country.

eNewsroom has tried contacting Deputy Commissioner, Giridih Rahul Sinha and sent a message too, but is yet to get a reply from him. Later his number was found switched off.

The officials not just tweeted to praise the PM but also forced private schools to lend their buses to ferry farmers. Such dictates were given in Bokaro too. Times of India did a story that in Ranchi, a large number of schools gave off and cancelled exam scheduled for September 12 as buses had been sent to ferry farmers and participants from various places to attend the PM’s rally.

And why dont you write a post when an IAS officer praises a congressi or a congressi govt